It took me five years to add 2.5kg to my total. Here’s what I learned.

In 2015, I put up a 347.5kg total. It was my first year of powerlifting and my second competition. Five years later in 2020, I finally registered a new PB total of 350kg. There were significant ups and downs across that five year period: great training blocks, horrendous ones, weight gain and loss, success in some lifts, major regression in others, injury and recovery, breaks from competition and breaks from structured powerlifting training altogether.

Even with breaks from structured powerlifting training, I lifted consistently four days per week this entire time. I trained hard. I poured a lot of time, effort and emotional energy in to my lifting. I had great coaches, physios and myos in my corner. And yet, I wracked my brain, unable to comprehend why things were going the way they were for me — everyone else had been making seemingly steady gains.

While sure, I’d love 20kg on my total, I am in hindsight appreciative of this experience: I’ve matured considerably as a lifter and just in general; powerlifting has taken up a really nice spot in my life among numerous other activities and pursuits that are meaningful to me; I’m a more compassionate coach and training partner. I’ve learned a number of lessons that I believe are immensely valuable for anyone experiencing their own seemingly endless and life-defining training plateau.

Some context before we dive in. Here are my competition results from the last six years. My squat has come a long way, my bench has come along, my deadlift has regressed terribly. I suffered from back pain from 2016 to 2019 and I pulled my hamstring at the end of 2019. Both will no doubt have contributed to the decline in my deadlift. I have no pain and am injury free now.

From my 347.5 total to my 350 total:

I added 7.5kg to my squat

I added 8kg to my bench

And I lost 13kg from my deadlift, lmao.

Open Powerlifting data.

So, on top of that whopping 2.5kg that I slapped on my total, here are some valuable insights I gained over that period.

You’ve gotta love lifting. If you don’t love it, you’ll never weather the storms.

I really love lifting.

Powerlifting has kicked me down more times than I care to make note of or admit. But the thought of not lifting just does not seem like an option to me. I cannot bring myself to abstain from the gym. Lifting just always feels good to me.

Therefore, no matter how long it takes or how long the plateau, I’ll improve eventually simply because I’ll continue pouring meaningful effort into that pursuit.

If I didn’t really really love lifting, there’s almost no chance I’d still be doing it.

If you’re only lifting for clout and success, you’re gonna have a really hard time gritting your teeth when the clout and success isn’t coming.

If you don’t love lifting itself and the process of seeking improvement — why are you doing it? How can you intertwine your why into the daily minutiae of lifting? And how can you enhance your enjoyment of the process?

These questions may not seem important when your training is going well; but they’ll become crucial in the face of any setbacks.

SBD isn’t the only measure of your development as an athlete.

There are many things you can improve at in your lifting career — load on the bar, sure. Technical proficiency in the powerlifts, sure. But beyond that — emotional maturity, resilience, work ethic, your ability to get up after failure, sometimes repeatedly. I’ve benefited immensely from developing these attributes, and from the carry over they’ve had to other areas of my life even while my total has been a complete flop.

And your total isn’t the only measure of your success.

In five years, I added 2.5kg to my total. It has not been the most objectively fruitful lifting career. But in that time, I’ve moved interstate, completed an undergraduate degree, launched and developed a successful business, grew a lot as a coach, fell for my best friend, celebrated four wonderful years with him, we adopted a baby bird and a kitty, purchased two properties, I’ve travelled to America, Uzbekistan, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Thailand, Vietnam, Germany, Croatia and the Philippines, and done a tonne of other cool shit too.

Lifting isn’t my only avenue for success or obtaining self-worth. My lack of progress on the platform does not reflect the progress I’ve made in life as a whole; nor does it have the power to weigh me down mentally — because I’ve diversified where I seek success and where I draw my worth from.

Everyone experiences plateaus; they just don’t always share them.

In the last five years, my squat and bench have had plenty of air time on the gram. My deadlift though, not so much. I’ve posted hardly any deadlift training and absolutely nothing from competition. I don’t want to share the shit parts of my training; nor do many other lifters.

And you can claim that I’m dishonest or deceptive for only sharing my highlight reel. You can claim that of many other lifters much better than me too. Because no matter how great the lifter, they’re human and have emotions too. They’re entitled to feel sad and not post up their most devastating lifts if they don’t have the emotional reserve for that.

It’s easy and common to feel very alone in your experience of a plateau; like you’re the only one not making gains when everyone else is seemingly killing it. Anyone who’s lifted for more than a year or two has almost certainly gone through a sizeable plateau. Only those that stay the course though are able to break through.

Your competition performance won’t always reflect the quality of your training.

You’re gonna have bad meets.

This is a tough lesson to learn, but one you’ll have to get okay with. Early in a training career, it’s common to view competition as the opportunity to PB at the end of a training block. But the fact of the matter is you won’t always register a PB in competition. Sometimes you’ll have a cracking training block and completely cook it on the day. You can throw it in after that. Or alternatively you can reflect on what the hell went so wrong, learn, move on and keep trying.

To tie this back into the top, this will be a lot easier if you enjoy training anyway, and derive meaning from it even when things aren’t going so well.

Your total PB will not necessarily reflect your success across each of the individual lifts.

If I could just hit each of my individual lift PBs on the platform on the same day, I’d have another 15kg on my total. But it is possible that I may never perform well in all three lifts on the same day.

Nailing 2/3 powerlifts isn’t a bad day. There’s maturity in wrapping your head around that.

You can have a good comp and not kill all three. You’ll enjoy the competition experience significantly more if you can adopt this perspective.

Comparison is the thief of joy.

There was a period of years in there that I unfollowed almost anything powerlifting related. I was so in my head. I’m almost embarrassed that this was necessary, but it was helpful and the outcome was positive so I feel it’s worth sharing.

When you’re new to lifting, you get newbie gains. They’re great, until they stop. When my gains slowed down and people around me were progressing and I wasn’t ranked well anymore, I lost my mind. I felt so inadequate in comparison.

To get over that initially, I did remove myself from the powerlifting landscape — I unfollowed lifters on IG and stopped competing for a while.

Returning a few years later, I was able to enjoy powerlifting so much more. With the lens of powerlifting as a hobby for me to enjoy that was not at all influenced by the enjoyment or success of anyone else, I can derive so much more enjoyment and fulfilment from the sport. I’m so glad I did that because I love lifting more than ever now.

Pain is largely psychological and that is a very valid and impactful part of the pain experience.

Your body may physically recover 100% from injury. And when that happens, your brain may not yet be 100% ready to go full send. Fear of pain or reinjury is a legitimate part of the pain experience, and one that should be acknowledged and attended to in your return to training and competition.

Rehab doesn’t need to feel like a waste of time and progress.

Rehab can be really fucking boring, I get it. But it’s much more boring being side-lined and not being able to lift at all.

I’ve found some degree of enjoyment and plenty of meaning by being a student of my rehab. I have learned so much from injury. My attention to detail is so much better for having that experience. I’m a much better lifter and a much better coach because I’ve been injured and I’ve had to do the physical and mental work to overcome that.

Be curious about your rehab, ask questions, understand what you’re doing and why. Not only will this help with your own buy-in and adherence, but it means you can gain even more from rehab than the huge win of your return to sport — gains you wouldn’t have made without that experience of adversity.

The journey is the destination.

I know, I know, this is so fucking cliche. But it’s cliche for a reason. Few people start lifting initially because they want to put up a fat total in competition and call themselves a champion.

For most of us, we start lifting for health, for fun, to improve our athleticism, to connect with like-minded people, etc. Don’t lose sight of these things when you start adding kilos to the bar.

Getting strong is cool, no doubt about it. But if you peel back the layers of what makes getting strong cool, for most of us you’ll find it’s things like developing mental fortitude, being able to get back up after failure, learning about yourself, meeting people who change your life, learning a skill, sharing a hobby with other people you love. Which leads me too…

Your training is not a waste if you’re not improving.

If you can align your focus to things like

Your enjoyment of training

Making new friends

Learning about yourself

Developing your work ethic

Becoming a tougher, braver, more resilient human

then no matter the length of the plateau, your training will remain meaningful and rewarding.

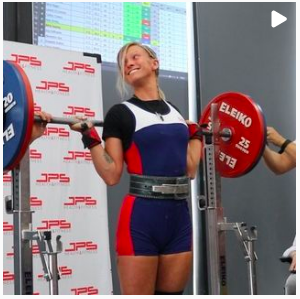

Here’s a walk down memory lane. All images link to their respective videos.

Squats

Bench

Deadlift

I love this stupid sport.